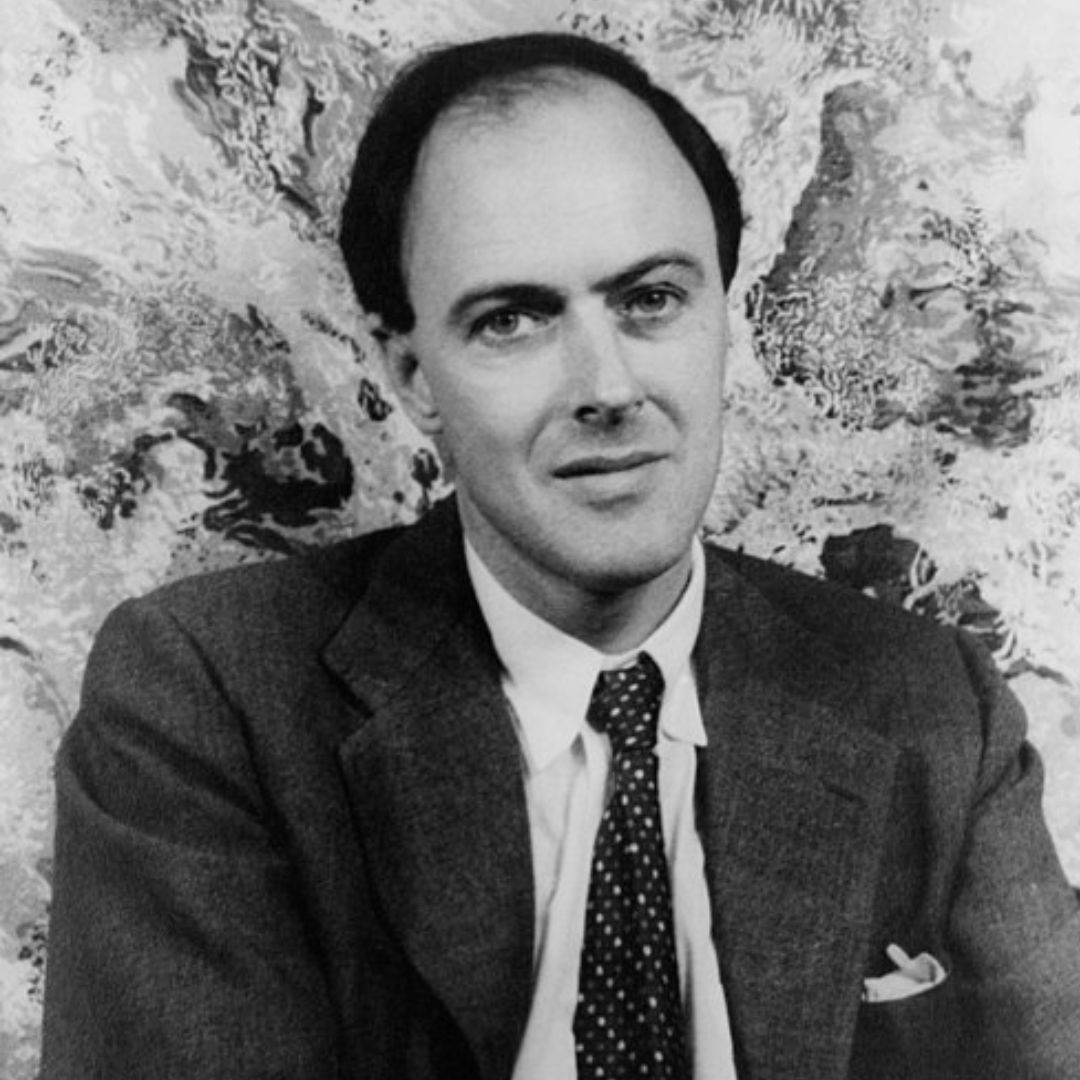

It is news these days that the heirs of the English writer Roald Dahl, in agreement with his longtime publisher Puffin (part of the giant Penguin Books), have agreed to modify the books of the famous children’s story author.

Specifically, it was decided to replace, in some texts, certain terms such as “dwarf,” “fat,” or the witch-woman correlation.

These words were allegedly deemed offensive by members of Inclusive Minds, an organization working in the field of inclusivity for children, from which Puffin sought advice. Indeed, the practice is becoming established on the part of publishers to poll so-called “sensitivity readers,” representatives of social groups or minorities, in order to identify alleged discrimination suggested by literary works and thus make them more palatable to the public.

Dahl’s books therefore, will be rewritten eliminating any reference deemed discriminatory to races, religions, or categories of people. The case is causing a stir in the literary world; already the writer Salman Rushdie, recently the victim of a religiously motivated assault, has spoken of censorship.

From a legal point of view, the fact invites reflection on a number of possible scenarios and, above all, on the issues of protecting the integrity of creative work and copyright.

We attempt an examination in light of Italian law.

A writer, when publishing his work, enters into a contract with the publisher for the assignment of rights (so-called publishing contract) governed by Articles 118 et seq. of the Law on Copyright (L.633/1941). Through this contract, the author grants to a publisher the exercise of the right to publish for print, on behalf of and at the expense of the publisher, the work of authorship.

As is always the case, it is only the so-called rights of economic use that are assigned, including the right to modify the work under Article 18 of the LdA. In contrast, moral rights of authorship are unsalable and remain with the creator.

In fact, this time Article 20 of the LdA, provides that

the author retains the right to claim authorship of the work and to oppose any deformation, mutilation or other modification and any act to the detriment of the work itself, which may be detrimental to his honor and reputation.

Note that Art. 20 also speaks of modification of the work but that it affects the moral sphere and not the patrimonial sphere as in Art. 18. Article 20 expresses the interest in the integrity of the work, understood as the author’s right to preserve the correct perception among the public of his own personality as expressed in the created work.

But what happens when the author is no longer alive?

Below, Article 23 of the LdA, specifies that after the death of the author, the right provided for in Article 20

may be asserted, without time limit, by spouses, children and, failing them, parents and other ascendants and direct descendants; failing ascendants and descendants, brothers and sisters and their descendants.

This is the first knot of the Roald Dahl affair: the heir is not conveyed the moral right mortis causa but rather he succeeds to the ownership of a right as if it were his own and which has as its object the respect and social esteem of a family member no longer living.

So, the constitutive and non-derivative nature of moral rights vis-à-vis heirs, which is provided for by law, by necessity is not reflected in the person of the deceased author, who, unless he or she has left written documents, can no longer manifest his or her will on any modifications of the work.

It then often happens that the heirs are completely outside the author’s areas of responsibility and find themselves administering his rights and the fate of his production. What will then should prevail?

The norm seems to leave no room for doubt; the heirs embody the will of the writer.

A not insignificant detail of the case, however, is that the heirs of the rights to Dahl’s works are no longer individuals but the Roald Dahl Story Company, a company that in 2021 was acquired by Netflix.

According to part of the doctrine of Law, integrity protection would find justification in a collective interest in the work itself, noted by the author, heirs or community. The basis of this interest would be found in many of the principles contained in constitutional norms, think of Article 21 of the Constitution on the freedom to express one’s thoughts.

How then, when the management of an author’s moral rights is affected by the interference of a legal entity with commercial purposes (in this case, the world’s leading distribution company)? Not least because, at the limit, the assessment of the injurious scope or, at any rate, the degree to which a creative work adheres to the values of the community that enjoys it, should not come from a “moralizing” entity that chases ever-changing trends and behaviors as society itself is.

Dandi Law Firm provides legal assistance in Copyright. Check out our Services or contact Us!