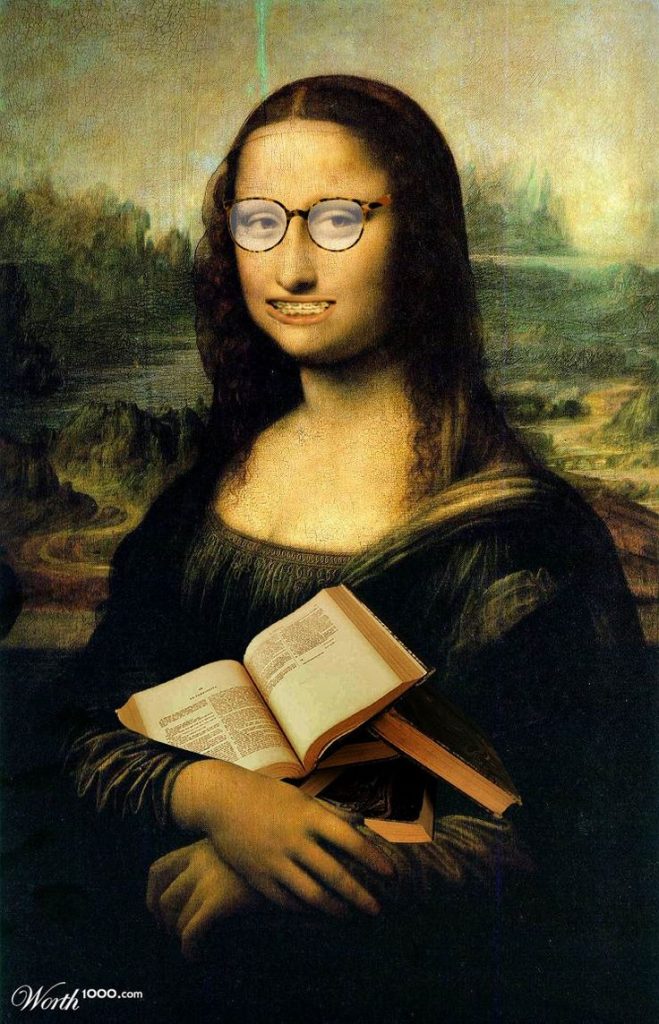

On 1 October 2014, the Government introduced new exceptions to the copyright law in the UK which now allows individuals to use copyright material for the purpose of ‘parody, caricature and pastiche’ without having to obtain permission from the original author.

Prior to this, any person who was using a parody, caricature, or pastiche of an existing copyright work would be held liable for copyright infringement if they had produced a substantial amount of the original work.

This was a major concern for those individuals who created parody work.

Blurred Lines: Ambiguity within the new framework

The European Copyright Directive provides no specific definition of the terms parody, caricature and pastiche and leaves it to the court to interpret the terms, although the IPO Guidelines set out explanatory notes for each term.

Parody imitates work for humor and evokes existing work while being noticeably different from the original. Caricature is something that portrays subject in a simplified or exaggerated manner. It may cause insult or compliments and it may be served for political purpose or for pure entertainment. Pastiche is musical or other compositions made up of selections from various sources or one which imitates the style of another artist or period.The new legislation provides that ‘fair dealing with a work for the purposes of caricature, parody, or pastiche does not infringe copyright in the work’.

Fair dealing is the crucial factor in the new exception yet holds no statutory definition. The IPO Guidance notes to the exception set out that fair dealing is a matter of fact, degree, and impression on each case. The courts have considered commercial factors, such as the degree to which the parody affects the market of the original work and any financial loss caused. They also undergo a quantitative and qualitative analysis relating to whether the amount of work taken is ‘reasonable and appropriate’.

Further IPO Guidelines cite that this exception is intended for ‘limited, moderate’ use of another’s material. Therefore, the parameters set by the exception are not entirely straightforward and there is no clear line drawn surrounding its application. Rather than rely on the new exception from the outset, if possible it would be advisable for the artist to obtain permission from the copyright holder. If permission is refused, the exception is still available. At this point, the artist can take steps to ensure the work is ‘fair’ and rely on the exception.

Copyright v. free speech in the CJEU

The Court of Justice of the European Union (the ‘CJEU’) considered the meaning of ‘parody’ in the case of Deckmyn and another v Vandersteen and others (C-201/13).

This case concerned the publication of a calendar which contained a reproduction of a drawing of the front cover of the Belgian comic, Spike and Suzy, which was published in the 1960s. Among other things, the copyright holders were opposed to the racial implications of the parody that demonstrated xenophobic tendencies.

The CJEU ruled that ‘parody’ must be regarded as an autonomous concept of EU law and interpreted uniformly throughout the European Union. They set out essential characteristics to classify parody:

(i) the evocation of an existing work while being noticeably different from it; and

(ii) constituting an expression of humour or mockery.

In addition to this, the CJEU stressed that the application of the parody exception must strike a fair balance between the interests of the authors and other copyright holders and the freedom of expression of the person intending to rely on the parody exception. While the Court doesn’t explicitly reference ‘fair dealing’, the protection of a legitimate interest suggests a similar interpretation to the UK exception. The CJEU concluded that a balancing exercise is to be applied by the national courts and must take into consideration all circumstances on a case-by-case basis.

While the uniform interpretation of parody within EU law provides a hopeful leaning towards certainty, the protection of legitimate interests is an issue left more open-ended by the CJEU. The Deckmyn case suggests that copyright holders can hold a legitimate interest to ensure that the original work is not associated with a discriminatory message. Yet it will be up to the national courts to determine what is discriminatory. This development may tip the scales in favour of the copyright holders.

The Deckmyn case, along with new exception introduced into UK law, seems to provide more scope for creative use of parody without infringement. However, it is unclear if this will be the end result depending on how the new UK exception and ‘legitimate interests’ held by copyright holders are interpreted by the courts. It could be argued that this balancing exercise may contradict the purpose of the parody exception and in fact, puts a strain on freedom of political expression within the use of parody. Conclusively, it is up to the national courts to strike a balance. However it remains unclear whose rights – the parody artist or the copyright holder – will outweigh the other.

The original article is in Italian. Sorry about that!

Dandi Law Firm provides legal assistance in several Practice Areas. Check out our Services or contact Us!